Contact the author and navigate this site

David Scott of Brotherton², Kincardineshire (2) b.16 June 1782 at Benholm, Kincardinshire, Scotland d.18 December 1859.

Son of David Scott of Brotherton, Johnshaven, Kincardineshire (1) b.1725 d.1797 and Wallace Scott More information

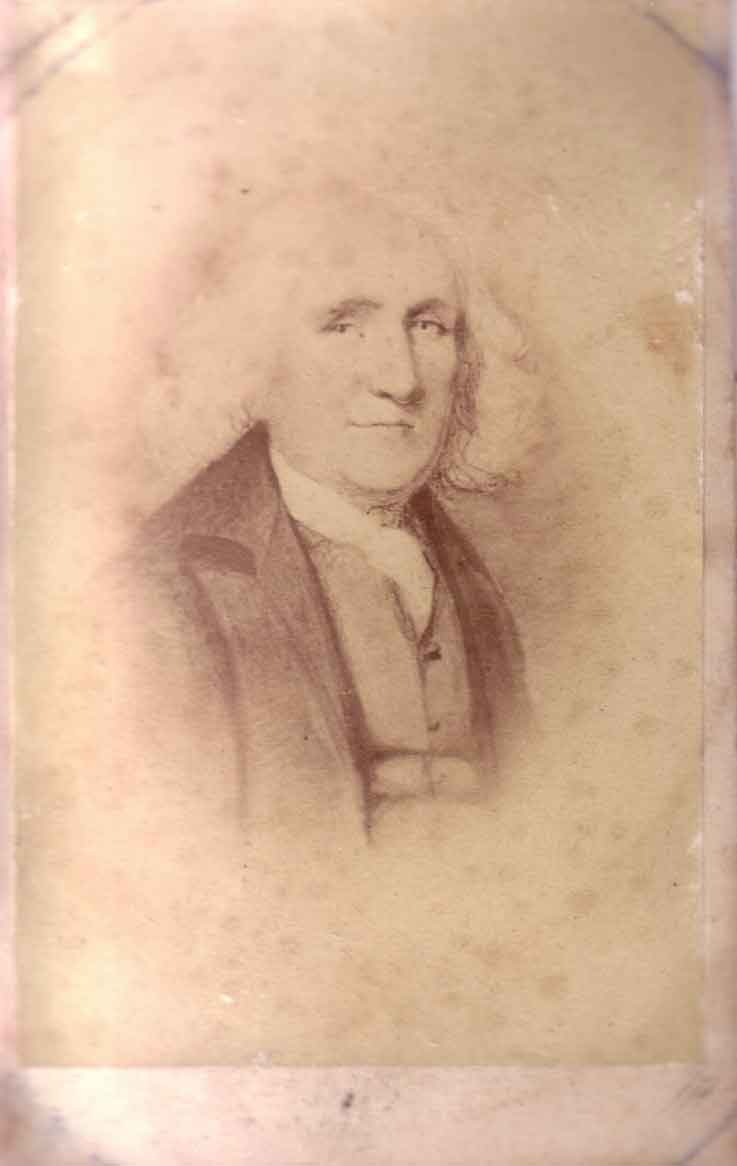

Married Mary Seddon b.1790 d.22 January 1866, daughter of William Seddon of Acres Barn, Eccles, Lancashire, son of John Seddon of Acres Barn, Eccles, Lancashire [picture], buried in Eccles churchyard, who himself was also father to General Seddon.

They had the following children:

F i Wallace Mary b.1815 d.1896

Married 10 Sep 1846 Reverend Walter Butler d.19 Feb 1857¹. They had the following children:

David b.1849;

Hercules b.1850.F ii Penelope b.1818 d.

Married (unknown) Dickson. They had the following children:

Sarah b.1844;

Selina b.1845.F iii Emily Augusta b.2 May 1822 at Ashton upon Mersey, Cheshire d.17 December 1899 at Sandbach, Cheshire.

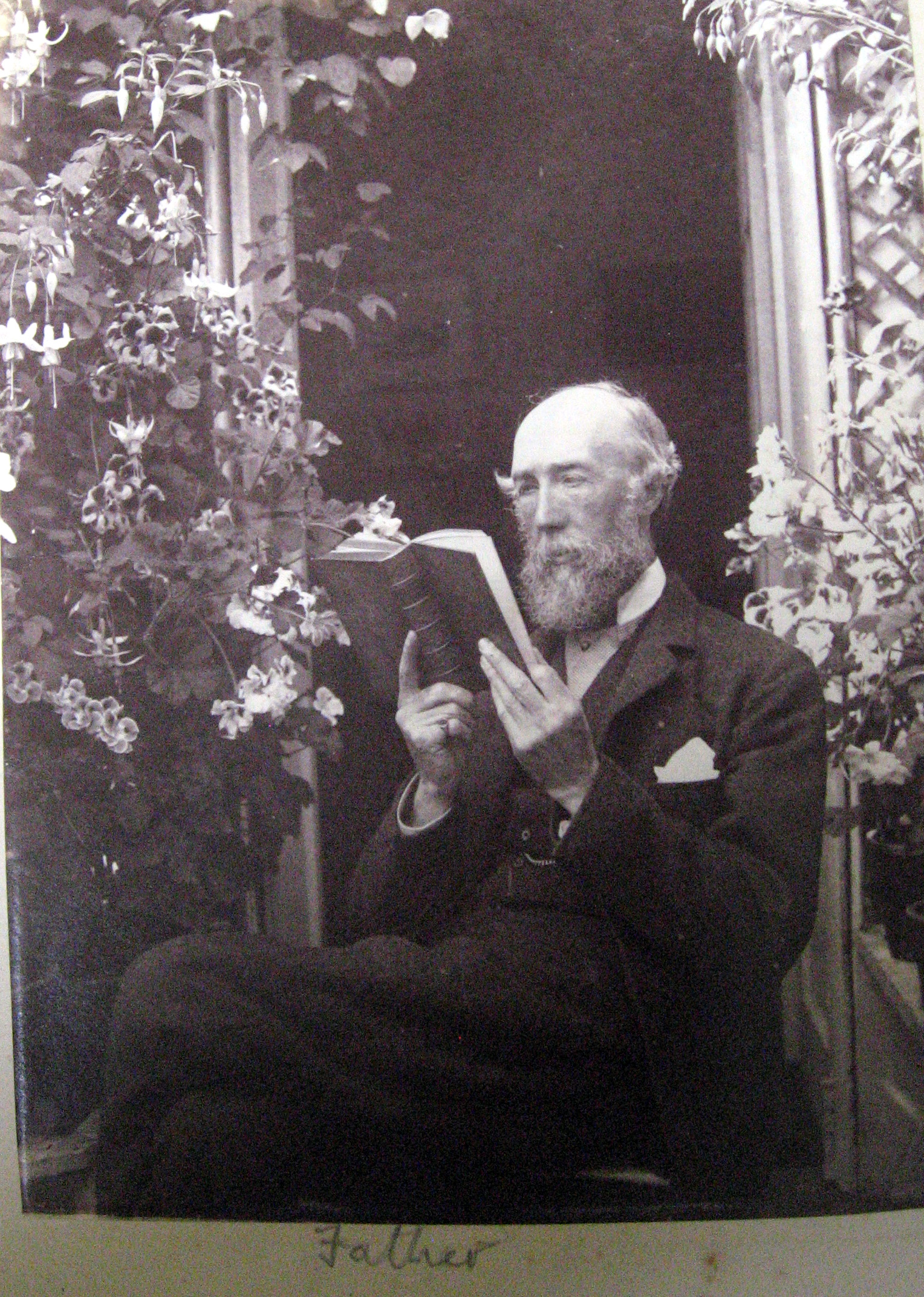

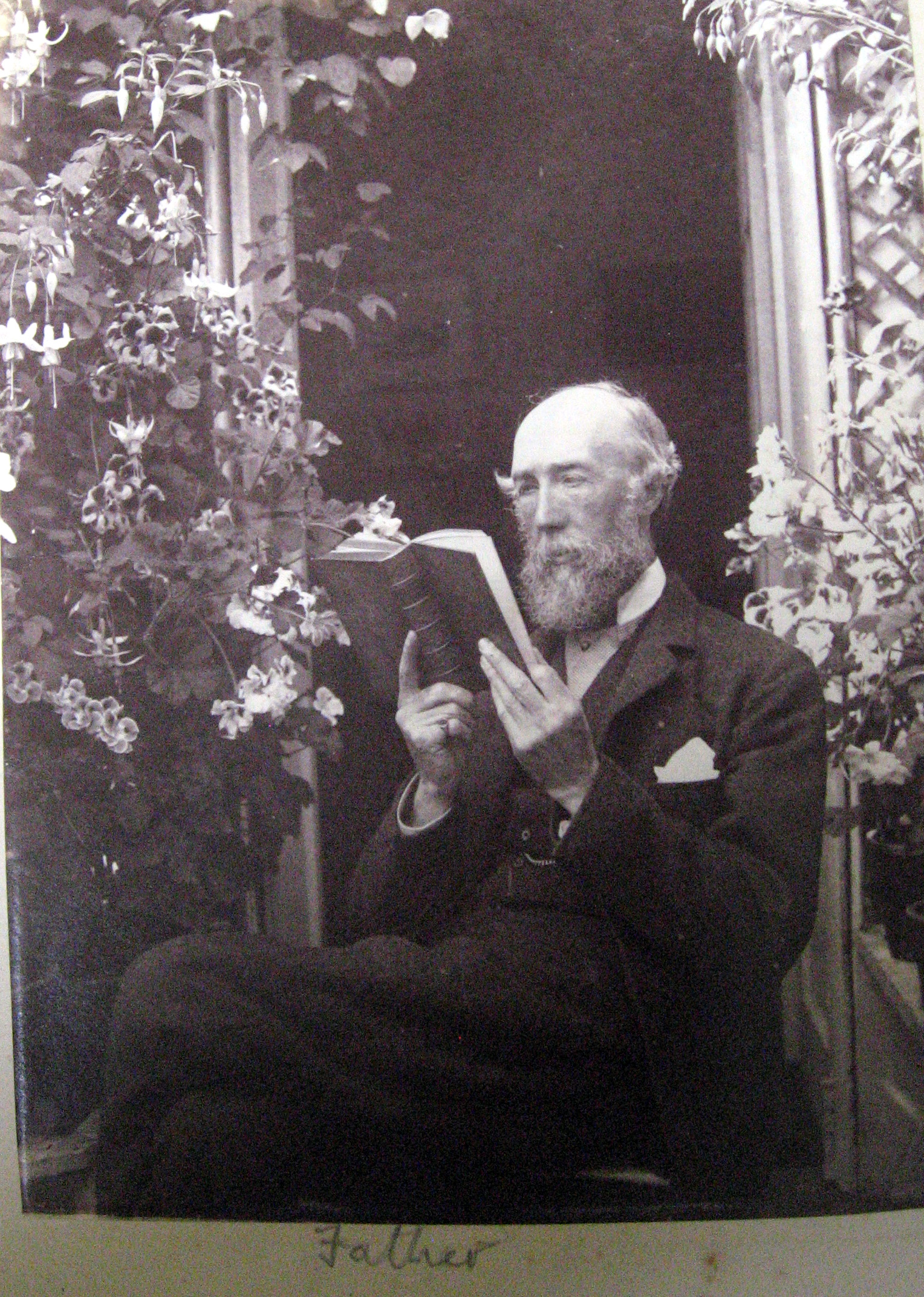

Married in 1842 Joseph St.John Yates b.10 October 1808 at Chancery Lane London d.1887 Sandbach, Cheshire.M iv Hercules of Brotherton, Kincardineshire JP [picture] b.15 Jun 1823 d.31 May 1897¹ More information.

Married 1857 Anna Moon b. d., only daughter of James Moon of Hillside House, Liverpool. They had the following children:

Hercules James b.1860 d.3 Feb 1869 of diptheria,

Mary Isabella b.30 May 1862 d.29 Jan 1869 of diptheria,

Helen b.12 Sep 1863 d.4 Feb 1869 of diptheria,

Edward Uchtred b.2 Feb 1865 d.1 Feb 1869 of diptheria,

Anna Katherine b.10 Jun 1868,

Margaret Rose de Noel b.25 Dec 1869.

Latter two daughters survived their father¹.F v Anna Maria b.1825 said to be 7th daughter, so there were three others

Married 16 Aug 1855 Cdr George Skene Tayler RN b.20 Sep 1816 d.18 Mar 1894¹.F vi Diana Octavia b.1829

Married 29 Apr 1863 James Farquhar b.16 Apr 1836. They had two daughters b.17 Sep 1864 (Reigate) and 5 Sep 1867.F vii (Unknown) b. d.

Married Edmund Lane b.1817. They had one child:

Katherine b.1844.

Other information Back to top of page

Hercules Scott b.1823

Hercules Scott was educated at Harrow and Haileybury College.

Deputy-Lieutenant for Kincardineshire. Lieutenant Commanding 2nd Kincardine

Artillery Volunteers. Entered Bengal Civil Service 1844, held various appointments

in NW Province including Settlement Officer at Salundhur, retired 1855. Chairman

of Montrose & Bervie Railway from 1855 until its sale to the North British Railway

in 1881. According to an entry in the Dundee Courier in that year, Hercules

was presented with a large oil portrait of himself by the Directors, which was

hung in Brotherton, but of which there seems no trace now¹.

A SHORT HISTORY OF BROTHERTON AND THE SCOTT FAMILY

Lathallan Preparatory School has occupied Brotherton Castle, the family seat

of the Scotts of Brotherton, for over thirty years. The building is not, of

course, a true castle at all; but is a Victorian mansion house built in the

Scottish Baronial style for Hercules Scott in the 1860's.

The connection between the Scotts and Brotherton goes back some three hundred

years before the building of the present castle. The estate of Brotherton was

purchased in 1570 by James Scott of Logie, a member of a cadet branch of the

family of Scott of Balweerie in Fife. That family, in turn, traces ancestry

to one Uchtredus Filius Scoti, who witnessed the foundation charter of the Abbey

of Holyrood House in 1128. Brotherton was presented by James Scott to his son,

Hercules, his other five sons being given the local estates of Craig, Commieston,

Hedderwick, Benholm and Logie.

Hercules the first of Brotherton resided in a building which stood where there

is now a terraced lawn in front of the present building. The original Brotherton

Castle is described thus in The Baronage of Angus and Mearns:

An old capacious mansion forming three sides of a square. The walls in some

places are about six feet in thickness. The older part on the East side as a

circular turret at the back which answers for a staircase inside. At the South

East corner there is a flagstaff attached.

Fortunately, Susan Carnegie, great grand-niece of Hercules, sketched the old

building in 1764, so we have some idea of what it looked like.

We now deplore the demolition of all old buildings; not so the Victorians!

The Stonehaven Journal of 2 June 1862 simply notes that the demoli¬tion

work and the building of the new castle would be "a boon to the neighbourhood".

The Scott family were very active in the area throughout the intervening centuries.

Susan Carnegie, nee Scott, was largely responsible for the founding of Sunnyside

Royal Mental Hospital and Carnegie House was named after her. Many other Scotts

made agricultural innovations. The turnip was first introduced to the county

by a Scott farming Milton of Mathers, who also developed the lime kilns there

and the salt pans at Usan.

Nor are the eighteenth century Scotts remembered solely for their land improvements;

there are reports, unfortunately unsubstantiated, of a connection with the Jacobite

cause. Scott of Logie owned a house in Montrose in which the Marquis of Montrose

was born and where the Old Pretender is said to have spent his last night before

embarking for France on 14 February 1716. The Montrose Review in December 1871

claims that he spent some time prior to that with Hercules at Brotherton. It

is certainly true that George Carnegie, Susan's husband-to-be, was on the rebel

side in 1745, living abroad in exile until he received full pardon in 1765.

As the Scotts achieved increasing status in the area, they adopted family mottoes,

Scott of Brotherton's being "paterno robore tutus" (safe by paternal

strength). They also received a grant of arms, emblazoned thus in The Baronage

of Angus and Mearns:

Argent a fesse embattled, counter embattled, between three lions heads erased,

Gules; in chief a mullet of the second, charged with a martlet, silver, for

due difference.

David Scott was the last occupant of the old Brotherton Castle. He founded both

St David's Chapel in Johnshaven and St Mary's episcopal church in Montrose.

He and his wife, Mary Sedden, had one son and eight daughters. The son was Hercules

who built the present castle. As a young man, Hercules spent some time in the

Bengal Civil Service, re¬turning home in 1850, and marrying Anna Moon, daughter

of a Liverpool cotton merchant, in 1857. The couple had five children before

their new home was built. After some years in temporary accommodation at Craig,

the family returned to Brotherton with considerable pomp. The Montrose Review

of 22 May 1868 claims that the event gave rise to "rejoicing at Johnshaven".

This may be connected with the reputation for philanthropy which Hercules was

fast establishing, including his founding of a soup kitchen for Johnshaven's

poor in winter 1866.

All did not go well in the new home, however. The four eldest children and a

nurserymaid all died between 29 January and 4 February 1869 from diphtheria.

The disease was believed to have been caused by the exposure of old drains during

the demolition of the old building. This left the fifth child, Anna Katherine,

and another child was later born, Margaret Rose de Noel, so called because she

was born on Christmas day.

With his brother-in-law, Mr Porteous of Lauriston, Hercules Scott was involved

in the creation of the branch of the North British Railway which ran between

Montrose and Inverbervie. Brotherton had its own halt. He also saw to the erection,

at a total cost of £300, of the St John's Templar Hail in Johnshaven's

"old" and "new" harbours in 1871 and 1884. The grand opening

took place on 5 July 1884 with a long procession from the harbour to the castle.

A painting of the harbour which can still be seen in the castle probably commemorates

this day. In accordance with his con¬cern for the local fishermen, Hercules

became involved in 1891 in the construction of a life-boat station in the village

to house the "Meanwell of Glenbervie". In 1891, this time on the instigation

of Mrs Scott, Johnshaven became the first village in the Mearns to boast street

lighting. In return for his generosity, Hercules Scott is said to have reserved

the absolute right to stop the Johnhaven mill from blowing its hooter as it

frightened his horses!

The castle which he built at Brotherton has been tentatively attributed to that

famous architect of the Scottish Baronial style, David Bryce, 1803—76.

It is constructed around a central hall, or "salon" which rises to

the full height of the building. The drawing rooms have ornamented plaster ceilings

on which the initials H. S. and A. M. are intertwined amid thistles and roses.

Much of the furniture was specially designed and gave its name to the Mahogony,

Birch and Pine bedrooms. The domestic quarters were comprehensive and included

a room set aside solely for storing vases and arranging flowers from the extensive

gardens. In the yard there hangs a bell, used for summoning servants and for

reminding guests when to change for dinner. Outhouses included several greenhouses,

an ice-house and a pagoda-shaped game larder. .

Hercules Scott was succeeded on his death in 1897 by his elder daughter, Anna

Katherine, the last Scott to live at Brotherton. Increases in taxation and real

wage levels in the new century, to say nothing of two world wars, brought changes

to all landowning families; but Miss Scott kept Brotherton intact until her

death. The estate was largely self- sufficient within living memory. It had

its own laundry, employing two maids, and its own gas-works, later converted

for electricity. The Mains of Brotherton was run by a grieve complete with dairy,

sawmill and blacksmith's shop. Before the last war, five gardeners, five foresters

and three gamekeepers kept the grounds in order, whilst, in the castle there

was a housekeeper, who acted as lady's maid, a butler, footman, hall- boy, cook,

kitchen-maids, house-maids and scullery-maids. After the advent of the motor

car, two chauffeurs were also employed, and in North Lodge there lived a gate-keeper.

A Christmas party was held for the staff every year, and in summer the gardens

were opened to the public. Various Sunday Schools held picnics on Laundry Park

where swings were erected. At the end of the day, all the children were led

up to the castle by the imposing figure of the head gardener and presented to

Miss Scott. They were then given a tour of the gardens before returning home.

Miss Scott was in the habit of renting a house in Chelsea for the Season, taking

with her her butler, cook, scullery maid, lady's maid and third housemaid. She

spent some time in London during the last war, allowing Brotherton to be used

as a maternity hospital. The first baby to be born there was presented by her

with a perambulator. Some three years after the end of the war, Anna Katherine

Scott died, in July 1948. Despite a lifelong membership of St Peter's and St

Mary's episcopal church in Montrose, she chose to be buried at Benholm. All

her staff were required to attend church at Benholm, and it is there that her

grave can be seen, along with other Scotts, in the family plot outside the East

door.

Brotherton was left to Miss Scott's niece, Mrs Freda Gell, who sold the estate

to Mr Charles Alexander. He gave it over to the use of Lathallan Preparatory

School in 1949, later selling the school governors the castle and its grounds

but retaining the farmland for his own use. Thus ended the unbroken line of

the Scotts of Brotherton. Appropriately enough, the new inhabitants also came

from Fife, seventy four boys under their head¬master, Mr J. H. Nock, refugees

from premises recently gutted by fire. Despite the fact that the stables have

now been converted into classrooms, the castle of Brotherton retains all its

original character.

PAMELA M. KING, 1980

The author wishes to thank all those who assisted her, particularly those who

gave her access to their persona! research and reminiscences.

¹Information via Mike Mitchell (Emails Sat 31-03-2012

15:49, Sat 31-03-2012 20:23 and 4-12-12 21:32) credited to the British Newspaper Archive, a

digital online archive service. Most of the entries are from the Dundee Courier.

John Seddon of Acres Barn, Eccles, Lancashire

John Seddon was also father to General Seddon. The caption

on the back of this photo says a miniature of General Seddon in Hussar uniform

is in the possession of the Whatton family.

From 'The annals of Manchester' edited by William E. A. Axon 1886 see Salford

Hundred ancestry:

Major-General Daniel Seddon, the youngest surviving son of the late Mr. John

Seddon, of Acres Barn, died May 18 [1839], in Paris, aged 78. Seddon, who was

educated at the Grammar School, entered the army and was several years in the

East Indies, and one of the few who survived thirteen months’ imprisonment in

the dungeon of Chiteledroog. He afterwards served in Russia and Egypt; and during

the rebellion in Ireland he received the thanks of the county of Antrim for

his defence of the town of Antrim from the rebels Sword in hand, at the head

of 26 dragoons, he charged the rebels, who had posted themselves to the number

of 500 in the principal street. He was one of the only three who survived. He

was afterwards appointed inspecting field officer in the northern district,

and had the rank of major-general conferred upon him for training Portuguese

troops.

A Seddon of Acres Barn, Lancashire appears as a witness in the marriage of Edmund

Greene Mahone Esqr. and Miss Margaret Rose Lewin both of the County of Clare

in the register of marriages in Portpatrick, Ireland (see Ulster

Ancestry). A Reverend Thomas Seddon of Acres Barn turns up in 1779 preaching

a sermon, mentioned in the 'The

Bayley family of Manchester and Hope'.

See also 'The Story

of Halshaw Moor Chapel' by Harold A Barnes, M.A., published in 1908 in by

J Whatmore, Printers, Bookbinders, Farnworth:

"1483 Adam Prestall owned land in Farnworth adjoining that of John Hulton and

Richard Seddon"

"In 1651 James Stanley Earl of Derby was executed in Bolton. It was reputed

as a fugitive he hid in the cellar of Seddon Farm, for a long time there was

a portrait of James Stanley there which has since been destroyed"

"...were the owners and proprietors of messuage, lands and tenements in the

manors, and, were thereby entitled to the rights of common upon the commons

and waste lands, which were in such a state as to be of little value, but if

divided into specific allotments and enclosed might be very considerably improved.

It was therefore elected that the several commons and waste lands (except the

moss or turbary grounds) should be set out, divided and allotted, and that.

John Seddon, yeoman, of Acres Barn, Eccles, Ralph Fletcher, yeoman, of Tong-with-Haulgh,

and Richard Jones, innkeeper, of Little Hilton, and their successors were hereby

appointed Commissioners for putting the Act into execution"

"The following paper does not treat of a resident of Farnworth, although his

home at Prestolee was only just across the boundary (being divided from that

township by the river Irwell), and his person and character were very familiar

to the inhabitants of Halshaw Moor, and there are no doubt some of the older

inhabitants of Farnworth at the present time who will remember him as “Dictum

Factum”. He punningly nicknamed himself “Dictum Factum” from Dictum — said,

and Factum — done — said done - Seddon, his real name being James Seddon.

He owned a paper mill which his father had previously worked, and his horses

and carts were frequently brought over Halshaw Moor over the old bridge at Darley,

to witch Mr. Rawson strongly objected, denying Mr. Seddon’s right-of-way over

that bridge, and threatened to forcibly contest it, if Mr. Seddon’s men again

made use of it ”Dictum Factum” (as he preferred to be called) soon gave Mr Rawson

an opportunity of putting his threat into execution, by sending his horses and

carts guarded by all the workmen he had in his employ. They were met at the

bridge by a staff of employees from Rawson’s chemical works, armed with a variety

of implements of warfare and a fierce battle ensued between the two parties,

ending in a complete victory for the Rawsonites, who thoroughly routed their

opponents and drove them back to Little Lever. No lives were lost, but there

were a few broken heads and many sore bones. “Dictum Factum” was terribly annoyed

and very indignant at his defeat, and revenged himself by getting printed and

extensively posted throughout Halshaw Moor and Little Lever a most bitter and

sarcastically placard, carefully worded so as not to be actionable. I well remember

the following lines in large capital letters: - ROAD STOPPERS AND WELL DESTROYERS

And some wag painted on the brew house door of the Church Inn: - “ In Memory

of Darley Fight”. And this remained on that door for several years, to the amusement

of persons attending the church, as there was no other way for worshippers to

the church than down or up Church Lane.

“Dictum Factum” was not only witty, but also whimsical and capricious. He had

a large summer house erected at the top of the large field leading from the

river, and on the top of this building he placed a large image representing

some celebrity or animal, which was changed every few weeks for a new one of

a different character, the dismounted one being broken up and thrown into the

river. He must have been a good Customer to some of the Italian image sellers

who at that time frequently came round carrying a large board on which ware

plaster images of various kinds.

He had an oil portrait painted, of himself which I thought was an excellent

likeness, but on exhibiting it to a party of visitors one of them (no doubt

mischievously) criticised severely, and found so much fault with it that “Dictum”

was thoroughly disgusted, and when the visitors left, he took a knife, cat the

picture out of the frame, and slashing it across several times he rolled it

up and ordered his servant man to throw it into the river, which was the usual

receptacle for most of his cast off hobbies. On the man and his wife and his

daughters examining the wreck they found to their great joy that the entire

features and one shoulder of the portrait are not injured, and James Leach who

was painting at Prestolee House at the time, brought the uninjured canvas home

to the Old Chapel lane, close to my father’s house. Leach, being an amateur

artist during his spare time from house painting, mounted the salvage portion

of the portrait on a large canvas, painted the missing parts of the picture,

and returned it to the coachman’s family, by whom it was highly prized. What

became of it in after years I do not know?

“Dictum” sometimes amused himself as a sculptor and prided himself in the bas-relief

figure of a horse, which he had carved and placed over his stable door. One

bright sunny morning he was showing some visitors over his establishment, and

calling their attention to the carving of the horse, told them it was his own

workmanship, when a Scotch gentleman of the party, rather banteringly, said

“D’ye call that a horse? Its nair like an ass with such long ears”, upon which

“Dictum”, looking down towards the visitor’s feet, hastily replied, with emphasis.

“Bless me, the man is looking at his own shadow”, and pointing at the stone

caving said “See you, man, that is what I directed your attention to, and not

your own shadow in the sunshine”.

“Dictum Factum” was a heavy shareholder in the old Bank of Manchester. When

the bank stopped payment a full meeting of the directors and shareholders was

held, at which it. Richard Roberts, the chairman of the board of directors,

presided. “Dictum Factum” entered the room just before the business of the meeting

commenced, and loudly announced himself thus: — “Gentlemen, I’ve come to show

you the biggest fool in all Christendom”, upon which one gentleman asked why

had (Mr. Seddon) risked such a large sum in a concern not considered over safe?

To which Mr. Seddon promptly replied. “Because the devil took me up into a high

mountain and showed me ten per cent.” This answer caused great merriment and

excitement amongst the assembly, upon which the chairman hastily called out

“Harmony, gentlemen, please, do let us have harmony”. “Yes”, replied “Dictum”,

imitating the chairman’s voice and manners, “It’s our money that we want, gentlemen:

please do let us have our money”. But they only received a very small portion

of their money, and many were thereby reduced from comparative affluence to

beggary and severe privations.

Some years before the bank’s failure, “Dictum Factum” had a new carriage built

according to a plan of his own, something after the style of Napoleon Bonaparte’s

private carriage which was captured after the battle of Waterloo and was afterwards

exhibited in London. When “Dictum” got his new carriage home, he invited my

father (whom he frequently came to hear preach) to accompany him for an hour’s

drive, then he would explain the various ingenious fittings and conveniences

the interior of the carriage contained. My father’s curiosity being excited,

he gladly accepted the invitation and ha was both amused and interested with

his ride. The description of the interior of the carriage and its cooking, citing,

and even sleeping appliances, would occupy too much space, but nothing seemed

to be wanting, that would add to the comfort of the traveller. This was previous

to the introduction of any railway. Shortly afterwards “Dictum” drove over to

his father’s, whom had retired to the suburbs of Manchester, and after showing

his father all the conveniences it contained the old gentleman said; “I’ll tell

thee what, James, if I had ridden in a carriage like that, thou would have had

to walk” a very pithy remark and full of meaning.

For many years after “Dictum” had retired from business he went to Manchester

every Tuesday to dine with a number of his old associates at the “Ship Inn”,

in Blue Boar Court, where there was a first-class ordinary every market day,

and he was a great gourmand, always enjoying a good dinner as well as cheerful

society. He had a rack fitted up in his barn at Prestolee, on which he had his

game (when in season) and sundry legs of mutton hung to condition and get tender.

He would never have a leg or shoulder of mutton cooked until it had been hung

in the barn at least a full fortnight after which he said, “It ate like venison”.

I remember “Dictum” coming to Mr. J.R. Barnes at the warehouse in Macdonald’s

Lane with a memorial or petition to the directors of the Manchester and Bolton

Railway, respecting the poor accommodation for passengers at Halshaw Moor Station.

This memorial he had embellished with a pen and ink drawing of a huge dragon,

with its open mouth representing the tunnel at Halshaw Moor, and of which issued

fire and smoke forming a locomotive engine, the body and tail of the monster

representing a railway train tapering off prospectively to little more than

a dot. Mr. J. R Barnes was one of the board of directors. We all had a good

laugh over this artistic and calligraphic curiosity after “Dictum” was gone.

During the last few years of his life, he grew to be enormously stout and short

winded. On one occasion he was returning from Manchester in the same compartment

I was in, and on arriving at Stoneclough Station, where his carriage was waiting

at the bottom of the steps, he had the greatest difficulty in squeezing himself

cut of the railway carriage, the doors being narrower than they now are now,

he was struggling to compress his huge corporation so as to permit his exit,

he caught sight of a “Manchester Guardian” which some one had left on the seat,

and turning to me he said, “That’s a ‘Manchester Guardian’ but this doorway

is a Manchester and Bolton guard you in”. A most atrocious pun, but it was certainly

impromptu.

One morning “Dictum” felt very unwell, and being of a very nervous temperament

he fancied he was going to die. He kept in bed and sent for his medical adviser,

Dr. Anderton, to come immediately, but the doctor had gone his morning’s round

of visits to his patients, and did not get home until noon then told “Dictum’s”

urgent message, the doctor hastily swallowed his dinner and hurried down to

Prestolee House. On his ascending the stairs, he heard preceding from “Dictum’s”

room, at short intervals, a long and prolonged Boo-oo-co-oo-m, followed in a

few seconds by another Boo-oo-oo-oo-m repeated several times. The doctor stopped

outside the bedroom door for a minute or two, listening to these strange ejaculations,

and entering the room laughing he approached the bedside and Inquired, “What

is the matter, Mr. Seddon? And what ‘is the meaning of all this?” The sick man,

turning a most doleful look towards the doctor said in a faint hollow voice,

“It is the passing bell tolling for the decease of “Dictum Factum”, who died

through the cruel neglect of Dr. Anderton”. The Doctor was highly amused, but

assuming as serious a countenance to he could, requested the sick man to put

out his tongue and hand, but “Dictum” refused, saying it was useless to feel

the pulse of a dead man, and taking a sovereign out of his purse, he gave it

to Dr. Anderton as his fee".

Daniel Seddon (1762-1839)

The following is a very long resume of his career from "Royal Military Calendar

- or - Army Service and Commission Book in 5 vols", 1820, London (Vol III p

249):-

"In 1778 this officer was a lieutenant in the Lancashire Militia and, in 1779,

Ensign in the 96th foot. In 1780 he was a Lieutenant in the late 100th Foot

under orders for embarkation on a secret expedition, which sailed from Spithead

the 13th March 1781, under command of General Medows and Commodore Johnstone;

this officer was engaged in the battle of Port Praya, fought at anchor in the

bay, yard-arm to yard-arm, with a superior fleet of the French, commanded by

Monsieur Suffrein, and which effectively frustrated the original intent and

purpose of the expedition, which was destined against the Cape of Good Hope

and Buenos Ayres. The French expedition, having taken possession of the Cape,

the expedition was obliged to proceed to the East Indies; on arriving there,

it being deemed expedient to divide the forces, a part went with General Medows

to the coast of Coromandel; the rest, consisting of the 100th Regiment, a part

of the 2nd Battalion of the 42nd, and two additional companies under command

of Lieutenant-Colonel Humberstone to the coast of Malabar. Destitute of every

necessary equipment for the field, they landed at Calicut in April 1782; a strong

garrison opposed their landing without effect, and the fort was immediately

stormed and carried with little loss. This small corps, after being recruited,

took the field and against every difficulty and impediment marched and raised

the siege of Tillicherry, which had been for two years invested by a powerful

army of Hyder Ali's under the superintendence of the late Tippoo Sultain. This

fortunate event enabled the garrison to spare a force of near 3000 native troops

well experienced in Indian warfare, which gave them the power immediately to

commence offensive operations. Lieutenant Seddon was at this period appointed

Brigade-Major to Major Campbell of the same regiment, who on all occasions commanded

the advance brigade.

The army was now somewhat formidable, near 1000 Europeans, and about 8,000 effective

Sepoys; with this force the campaign was carried on with the utmost energy,

and during which they possessed themselves of every fort and garrison from Tillicherry

to Anjanga, and from the coast to Ramghurry. Several general engagements were

fought, and the almost daily skirmishing perfectly established the credit of

this little army for bravery, discipline and patient endurance.

The services of this officer in the following campaign were required as an engineer.

The field was taken even before the monsoon had ended, with every prospect of

brilliant success, for notwithstanding the torrents of rain which fell, and

the incessant opposition which was made, they fought their way to Pallachacherry.

This movement was made with the intention of giving relief to the Carnatic,

and it had the effect of withdrawing Tippoo Saib in person, with 30,000 troops.

The moment intelligence to this effect arrived, an instantaneous retreat was

ordered, but no sooner had the troops re-entered the town, which they had before

passed through without even leaving a guard therein, than they were attacked

on every side, front, flank, and rear, as well as from the windows and roofs

of the houses. In this perilous state they remained for several hours, nor were

they able to extricate themselves until the evening closed, when a passage was

forced, but at the expense of many valuable lives, both of officers and men,

with every article of baggage, provisions and ammunition, except what had that

morning been served out to them. The battalion guns fortunately escaped, which

in a great measure saved the army. The wounded, such of them as were unable

to walk, were of necessity left in the streets and in this state, under constant

heavy rain, the march was pursued. It was so far fortunate however, that the

rain continued with such unremitting violence, as to impede the rapidity of

Tippoo's movements, and thereby saved the lives of numbers, and probably the

entire army. Under such uncommon difficulties it was most wonderful that the

retreat was effected at all - not a moment's time to halt, no possibility of

cooking the scanty provisions the troops had with them, and the enemy hanging

on their flanks and rear. Ten days however completed their march, but so utterly

exhausted were they on their arrival at Panana, their depot, that they laid

themselves down in the sand, and would have suffered death rather than have

been at the trouble of rising to defend themselves. The next day however presented

a different view - a British fleet was anchored close to shore, from which Lieutenant-Colonel

M'Leod landed with the remainder of the 42nd regiment, and about 2,000 additional

Sepoys. This seasonable relief gave confidence to all, provisions were served

out, and all was joy, exertion and bustle. Breastworks were forthwith thrown

up, and every man laboured with all his might. It was evident that the enemy

were fatigued, or that the whole of their force had not yet arrived, otherwise,

had they sooner commenced their attack, they most assuredly would have had infinitely

greater advantage, but they suffered three days to elapse, and in that time

everything was prepared to give them a warm reception.

At daybreak on the fourth day the enemy's entire force, commanded by Tippoo

in person, commenced a general attack, and were repulsed in every quarter with

considerable loss. This so enraged His Highness that, when he rallied, which

he had a difficulty in doing, he recommenced the attack, and placed his war-elephants

in the rear of his own troops, at the same time giving them to understand that

inevitable death would be the consequence of their retreat. A desperate assault

again took place, and they were again repulsed with immense slaughter. The confusion

they were thrown into by the bayonets in the front, and the elephants in the

rear, occasioned the Sultaun a loss of upwards of 5,000 of his best troops,

a greater force than the British had in the field. Whether this complete defeat

or the death of Hyder Ali, which happened at that time, induced a precipitate

retreat was never ascertained, but the following morning the whole army had

disappeared. A few days after this glorious victory the troops embarked and

proceeded coastwise, to meet a force then expected under the command of Brigadier-General

Matthews. The junction was formed at Sadashagur near Goa, and the whole were

landed with but trifling opposition. Lieutenant Seddon now returned to the duties

of his regiment, which was actively employed on every occasion and on every

emergency. In a short period this army, now nearly 8,000 men, over-ran the whole

coast, took every important garrison, and the strong forts of Onore, Cundapore,

Cannanore and Bangalore fell into their possession. From Cundapore their course

was directed to Bedanore, with the intention of again relieving the Carnatic.

Every possible resistance was made to stop the progress of their march which

the enemy finding impractical, resolved to make a desperate stand, for which

purpose they collected all their strength for defence of the Ghauts, which were

nearly a perpendicular height with five barrier gateways, yet nothing could

withstand the intrepidity and bravery of the troops. They stormed and, at the

point of the bayonet, carried the whole in less than three hours. Lieutenant

Seddon was on this occasion slightly wounded in two places, but not so materially

as to prevent his continuing his services. These gallant achievements ought

to have been recorded by earlier historians, but the subsequent calamities of

the army, and being afterwards captured, prevented them from being particularly

known. The enemy, panic-struck by what they considered so desperate an undertaking,

surrendered Bedanore without firing a shot. Ananpore and Cooladroog were taken

by storm, and an immense extent of country was taken possession of. These brilliant

successes however were not of long duration, for Tippoo Saib, now Sultaun Bauhauder,

having by the death of Hyder Ali quietly succeeded to his dominions, and finding

his richest provinces overrun by a comparatively trifling force, moved an army

upon them of 40,000 men and a corps of French, commanded by Colonel de Cossigné.

A disagreement having taken place previous to this, between General Matthews

and the field officers of his army relative to the division of the spoils of

Bedanore, the whole were sent away, and lucky indeed it was for them.

On the approach of Tippoo and his army, the general moved all his force, now

not more than 1,500 men ( the rest having been left in different garrisons)

to meet the enemy in the open plain. This extraordinary conduct occasioned a

severe loss, and reduced the remaining few to the confines of the fort; the

siege lasted 17 days, a cessation of arms took place, and on the 26th day of

April 1783, this gallant army terminated their exploits. The garrison capitulated

on the following terms:- That it should march out of the fort with the honours

of war, and pile their arms on the glacis; the public stores and prisoners to

be given up, private property respected and that, after the garrisons of Ananpore

and Cooladroog (which were included in the articles) had joined, the whole should

be at liberty to proceed unmolested to Sadashagur, a sufficient guard to be

furnished for their protection, and every necessary accommodation given for

the comfort and convenience of the sick and wounded, and that two hostages should

be sent forthwith by the Sultaun for the performance of the articles on his

part. The hostages were forthwith sent, the capitulation signed and the troops

accordingly marched out of the garrison and piled their arms on the glacis.

They were then surrounded by a large body of the enemy, which was supposed for

their escort, and conducted to a plain about half a mile from the town, where

they remained without notice or shelter till the 1st of May. The most gloomy

presage now pervaded everybody. The General, the Captains and all the principal

officers were sent for and the remaining British or European officers were ordered

into the bazaar. Here the most disgraceful and ignominious scene took place

that was almost ever witnessed: one by one they were forced into a circle of

armed men, and there stripped and plundered of every article that was worth

consideration, nor did they scruple at exposing them thus naked, to the ridicule

and insults of their brutal banditti. The women also were searched in the same

infamous and indecent manner. In the afternoon the European soldiers and Sepoys

were separated, the sick and wounded were left to perish on the ground, and

in the evening the subalterns were marched into the stables which their horses

had occupied but a few days before, and there more closely confined, without

food, until the following night. A pice and a seer of the coarsest black rice

was then given to each person. On the 7th a letter was sent to the Commandant

of the French troops, Monsieur Cossigné, praying his inter-ference with the

Sultaun, representing to him the shameful violation of the conditions on which

the fort surrendered, and the cruel and inhuman treatment they experienced,

requesting him at the same time, in the name of his Britannic Majesty, to use

his strenuous endeavours that the terms of the capitulation be adhered to and

if he, in that point, failed, that he would for humanity's sake obtain a mitigation

of their hard usage. This letter was never answered but they were told that,

as General Matthews had plundered the treasury and stores, the Nabob considered

himself justifiable [sic] in acting in the manner he did.

On the 9th the subaltern part of that brave army were removed in pairs from

these loathsome stables, rendered insupportable by the dreadful stench that

arose from such close confinement, and were, at the door, linked together like

felons with irons so rough and unfinished that, in a short time after they were

thus manacled, but little skin was left on their wrists. When the whole were

fitted with serviceable heavy irons, they were marched, like convicts to the

galleys, to pass in grand review before His Highness the Nabob Sultaun, where

they were received with shouts of joy and acclamations of the most malignant

inveteracy. At 7 o' clock on the morning following, their march was commenced

under a strong escort of infantry and cavalry, each officer as he left the ground

receiving three pice (about 3 farthings) for his day's subsistence. To detail

every barbarous and inhuman aspect of this march would overpower the feelings

of humanity: we will therefore content ourselves with stating that a number

died for want of food, from savage treatment and from intensity of the heat.

It was the misfortune of Lieutenant Seddon on this occasion to be handcuffed

to an officer who died, but the barbarians would not liberate him from the corpse,

and, placing it across a bullock, obliged him to march by its side till the

day's journey was ended. On 21st May this miserable body of fallen heroes arrived

at Chittledroog and, after having been exhibited for several hours to the gaze

of the gaping multitude, they were marched to the summit of this almost impregnable

fortress where they were formed into two divisions and put into several cells.

Their handcuffs were then taken off and heavy irons put upon their legs. We

will pass over their wretched condition in this abode of misery, briefly observing

that during the whole period of their confinement they were kept under continual

apprehension of their being either poisoned or starved to death for want of

food. Providence however ordained it otherwise for, on the 25th March 1784,

their irons were knocked off and they were taken out of their dungeons. The

prison in which Lieutenant Seddon was confined consisted of four dark rooms

surrounded by a wall of twenty feet high, which formed an area of four yards

square and was the only place that nine and thirty of them had for every purpose.

At one time they were kept for three days without provisions, but they suffered

no inconvenience on that account, having a plentiful supply of rats on which

they fed.

When they were moved into the open air and quite at liberty, they were unable

to walk from their legs having been so long and so closely confined together.

Here they were joined by their fellow sufferers, who had survived the hardships

of the other prison but alas, like themselves, in so meagre and miserable a

state that even the most intimate friends did not know each other, and at which

the reader will not be astonished, if he considers their long confinement, almost

entirely naked, their beards at full length, their hair matted and their bodies

covered with vermin. Such however was their sensations at this meeting, that

tears of joy trickled down their faces. About eleven o' clock the whole were

ordered to proceed below, but which, with every possible exertion, they were

unable to effect before 10 o' clock at night. The next morning they were informed

that a peace had been ratified between the Sultaun and the East India Company

and that they should be immediately conducted to their own country.

On the 28th, somewhat recruited both in body and mind, they began the happiest

march they had ever as a body taken. On 25th April they reached their own territories,

and were on that day given up at Vellore, one of their frontier garrisons in

the Carnatic. Dreadful to relate, General Matthews and every officer, save one,

above the rank of subaltern had been most barbarously and inhumanly murdered.

We will not dwell on this sad and melancholy subject, but shortly state the

losses which the 100th [Regiment] alone sustained during the short period of

its existence. They were raised by Lieutenant-Colonel Humberstone the latter

end of the year 1780, sailed for the East Indies the beginning of 1781 and,

on the 25th April 1784, the day on which they were given up, they had lost by

service:-

1 Lieutenant-Colonel

3 Majors

7 Captains

16 Lieutenants

9 Ensigns

1 Quarter-Master

1 Surgeon

1 Surgeon's Mate

- and upwards of twelve hundred men

Such a list of casualties in one regiment, and in so short a time, perhaps was

never known. They were embarked upwards of eleven hundred strong, had two additional

companies drafted into them, and some recruits joined them from England, and

they returned to their native land in 1785 with only 27 men. Four Captains suffered

death by poison, the vacancies of which, as well as every other that occurred

during the captivity of the regiment, were filled up in England. However, immediately

previous to the reduction of the regiment, the Captain-Lieutenancy became vacant,

and this officer succeeded thereto. We have exceeded the limits of our wishes

in detailing so particularly the services of this unfortunate regiment but we

have been induced to do so in consequence of its having been so long in confinement,

and the peculiar hardships which it underwent being but little known.

This officer, during the time he remained on half-pay, made an excursion to

the northern continent, and visited Germany, Denmark, Sweden and Russia, where

he availed himself of every opportunity of obtaining professional knowledge.

In 1788 he was recalled from his tour, having succeeded to a company in the

75th Regiment [the Highland Regiment], and again went out to the East Indies.

This Regiment, raised by its present Colonel, Sir Robert Abercromby*, was considered

one of the best disciplined in His Majesty's service. Certainly it produced

some officers of considerable eminence, among whom were Major-General Robert

Crauford, Lieutenant-General Sir Samuel Auchmuty* and General the Honourable

John Abercromby*. [*All in New Oxford Dictionary of National Biography] Captain

Seddon went through the regular service with this regiment as Captain of grenadiers,

and was at the taking of Seringapatnam with Lord Cornwallis [as was his nephew,

Edward Boardman]. In the year 1792, in consequence of a universal peace, and

being unable to obtain leave of absence, he disposed of his commission and returned

home, but on his arrival the French revolution had broken out [hardly - it broke

out in 1789. In 1792 Louis XVI was found guilty, later to be beheaded, which

is what may be referred to here] and he re-commenced his services.

In 1795 the 22nd Light Dragoons, in which he was then Major, embarked for Ireland,

and in the rebellion of 1798 he was stationed with a squadron of that regiment

in Antrim. The circumstances attending the attack of that town are too well

known to require mentioning; suffice it to say the 22nd suffered materially

and the rebels very considerably. Major Seddon on this occasion was wounded

and had two horses shot under him, one of them in three different places. His

conduct during his stay in this troubled part of the country was most highly

spoken of, and the loyal inhabitants of the town and neighbourhood testified

their approbation by presenting to him a piece of plate [mentioned in the codicil

to his will] estimated at 300 guineas value, and on which was engraved the following

inscription This Piece of Plate is presented to Daniel Seddon, Esquire, Major

of the 22nd light dragoons, by the Inhabitants of the town and neighbourhood

of Antrim, as a mark of gratitude, for his unremitting attention to the preservation

of their lives and property, in bringing treason to justice, and affording protection

to loyalty, during the period of near four years which he commanded in this

district. Antrim, July, 1798.

On 1st of January 1800 he obtained, by brevet, the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel,

and early in 1801 he embarked with the regiment for Egypt, and remained there

until the end of the war. On their return home the regiment was disbanded [the

short-lived Peace of Amiens] and when the war broke out again he was appointed

Inspecting-Field-Officer of Yeomanry and Volunteers in the Northern District,

in which situation he remained till 1809. He then went out to Portugal and commanded

the 1st Brigade of Portuguese cavalry. On obtaining the rank of Colonel, the

25th of July 1810, he returned home and on the 4th of June 1813 he succeeded

to the rank of Major-General."

Notes:

- A brevet rank was a rank without the full complement of troops to go with

it, and usually given as a mark of distinction.

- Chiteledroog was Chitradurga Fort in today's Karnataka - a huge, sprawling

and all but impregnable fort.

- Seddon claimed in WO 25/748 (48) that he was without pay for a year and a

half. This was during the period of his imprisonment - which does seem extraordinarily

mean-spirited and callous on the part of the army. It still rankled with him

forty years later.

- His conduct at the Battle of Antrim (1798) might have been heroic, but it

was exceedingly stupid. To charge down a long street lined with houses really

isn't too smart and, when you find there is no-one at the end of it, and have

to charge all the way back again, well......

- The "Rebellion" was that of the United Irishmen of that year.

- The Dragoons were of course of the 22nd Light Dragoons. Citation is the London

Gazette of June 9th 1798 - he was mentioned by name and rank in the Gazette

issue of 12th June.

- Contrary to any claims he was not at the battle of Waterloo.

- it is interesting that Seddon's way of dealing with what we today would call

Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, after his captivity and privations, was to travel

extensively. I would hazard a guess that he could not, for a long time, bear

to sleep in the same place for very long. God knows how he coped on board ship

on his way back to Blighty.

As far as the entry itself is concerned I have reproduced it word for word.

However the punctuation is eccentric to say the least. The writer obviously

thought full stops were the invention of the devil and colons were all the punctuation

a gentleman ever needed. This was merely the most obvious of the eccentricities.

I have therefore completely re-punctuated it. The other thing to say is that

two things amazed me. The first was the depths of stupidity, over-confidence

and neglect of even the most elementary precautions displayed by the senior

army officers involved. The second was the degree to which the narrative, even

allowing for the fact that it is in the great tradition of Medieval hagiography,

is dominated by the writer's narrow outlook on the subject matter. There is

not the slightest inkling that he (one assumes it was an 'he') might even have

considered that, if an enemy army invaded your country for extremely dodgy reasons,

you might feel both at liberty to destroy it by every means at your disposal

and teach the invaders, and others who might be disposed to do likewise, a lesson

they would not easily forget. Not that this, to us understandable, mind-set

availed them any once a proper, if unlucky, general appeared on the scene.....

Hans Norton

July 2010

Reverend Thomas Seddon (1753- 1795)

The following is the text of the entry in the New Oxford Dictionary of National

Biography, written by Mark Smith

Seddon, Thomas (1753-1795/6), Church of England clergyman and author, was born

at Acres Barn, Pendleton, Lancashire, the son of John Seddon, farmer, of Pendleton.

He received his early education at a number of local schools, including the

Manchester grammar school. He was intended by his father for the medical profession

and at the age of seventeen was entered for training at the Manchester Infirmary.

His own aspirations, however, lay towards the church and while still at the

infirmary he received an education in the classics under the tutorship of the

Revd John Clayton of the collegiate church in Manchester. Encouraged by a promise

of preferment from a certain baronet, he entered Magdalen Hall, Oxford, as a

gentleman commoner, matriculating in 1776. He does not seem to have taken any

degree and according to his own account was not much benefited by an academic

education but he obtained a testimonial and without difficulty was ordained

a deacon in 1777 and priest in 1778. The original promise of preferment was

not fulfilled, and a combination of improvidence and the expense of his education

left Seddon in debt. He sought to resolve his financial difficulties by making

an advantageous marriage and on 2 October 1777 married Margaret Sidebottom,

a young lady of good family near Manchester. The marriage seems to have proved

a disappointment to both parties-there were no children-and seems effectively

to have terminated by separation before 1786.

Seddon's early career in the church was also a disappointment. In 1779 he was

licensed as incumbent of Stretford, a small living in which he had served as

curate since 1778, and in 1781 was also offered the new living of St George's,

Wigan. However, his living at Stretford was sequestered for debt after he had

been there two or three years, while opposition from an influential group of

parishioners in Wigan obliged him to give up St George's. His reputation was

further damaged by his publication in 1779 of Characteristic strictures, or,

Remarks on upwards of one hundred portraits, of the most eminent persons in

the counties of Lancaster and Chester: particularly in the town and neighbourhood

of Manchester. This work, penned under the influence of multiple disappointments

and published anonymously, consisted in a number of satirical and libellous

sketches of local notables and gave great offence.

After the sequestration of Stretford, Seddon appears to have sought to supplement

his income by writing and by serving as chaplain to the earl of Lonsdale. In

1786 he published his most significant work, Letters written to an officer in

the army on various subjects, religious, moral, and political, with a view to

the manners, accomplishments, and proper conduct of young gentlemen, in two

octavo volumes. This work, probably addressed to his brother the future Lieutenant-General

Daniel Seddon, together with his other published output (a number of sermons

and a volume of 1780 entitled Impartial and Free Thoughts on a Free Trade to

the Kingdom of Ireland) reveal him generally to have been a man of conventional

high-church tory views.

Although in the autobiographical introduction to the Letters Seddon described

himself as retired from all professional engagements and without hope of succeeding

to any, his career seems to have revived in 1788, when he was nominated to the

perpetual curacy of St Anne's Lydgate in Saddleworth, which he held in plurality

with Stretford. The living was poor, however, and his debts continued to increase.

In the 1790s he was prominent in co-ordinating anti-radical activity in the

area and in 1794 he became chaplain to the 104th regiment of foot, the Royal

Manchester volunteers, before leaving in 1795 to join the regiment at Belfast.

He met his death by drowning, possibly with men from the regiment who had been

transferred to an expeditionary force to the West Indies and whose transport

was lost in a gale on 18 November 1795 near Portland. No notification of his

death, however, reached Manchester before May 1796, and its precise date remains

uncertain.

Sources

+ T. Seddon, Letters written to an officer in the army on various subjects (1786)

+ C. C. W. Airne, St Anne's Lydgate: the story of a Pennine parish, 1788-1988

(1988)

+ F. R. Raines, 'Catalogue of incumbents of Lydgate', Chetham College Library,

Raines MSS, 15.57

+ J. F. Smith, ed., The admission register of the Manchester School, with some

notices of the more distinguished scholars, 1, Chetham Society, 69 (1866)

+ J. Bailey, Old Stretford (1878)

Wealth at death probably in debt: Airne, St Anne's Lydgate

Contact the author and navigate this site

Want to ask questions, offer information or pictures, report errors, suggest corrections or request removal of personal information? Contact author

Notes on sources

Anderson family tree

Information is largely taken from the book 'The Andersons of Peterhead'. This was based on the records made by John Anderson 1825/1903 [VIII 32], known as 'China John'. This was brought up to date in 1936 by Cecil Ford Anderson [X 17] and Agnes Donald Ferguson [CS 45 X b]. Many photographs were taken and compiled in an album by Olive Edis (daughter of Mary Murray, daughter of Andrew Murray (2) of Aberdeen). Corrections to both Janet Innes Anderson's and Alexander Murray's death dates from Robert Murray Watt and Iain Forrest.

Forrest family tree

Iain Forrest kindly supplied material to update the Forrest family (progeny of William Forrest) details.

Hibbert family tree

The information is largely taken from a tree compiled by F.B. (she knows who she is!) with extra material found by the author.

Murray family tree

The 'Genealogical Table showing various branches of the Murray family', from which this information was taken, was prepared by Alexander Murray of Blackhouse, extended by Andrew Murray - advocate - Aberdeen circa 1880 and further extended by Arthur Murray Watt 1972. The generational notation is the author's.

Pike family tree

Information from family sources as well as 'Burke's Landed Gentry' 1875

Stevenson family tree and many Stevenson and Anderson photos

Deepest thanks for some fantastic pictures and for writing the wonderful book 'Jobs for the Boys' to Hew Stevenson, which you can see on www.dovebooks.co.uk.

And the rest

Thanks also to all who have written in with information, advice, help and, most importantly, corrections.

© John Hibbert 2001-2013

28 February, 2021