Son of Alexander Anderson (6). b.1808 d.1884 and Mary Gavin b.1806 d. 1864 aged 57, the third of eleven children of Dr Alexander Gavin, R.N., medical practitioner at Strichen, naval surgeon on H.M. Frigate "Arrow". More information

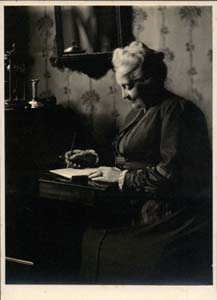

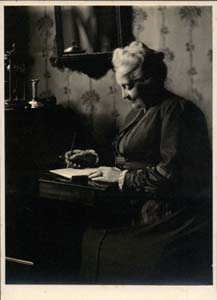

Married in 1872 Gabrielle Coudron of France b.1850 d.1929 aged 79 [pictures] [more information], daughter of Amédée Coudron [picture].

They had the following children:

Other Information Back to top of page

M i Cecil Ford b.1872 d.1946 [picture] . Royal Engineers, built the railway up the Khyber Pass.

Married [picture] in 1909 Maud Alice Bellingham, daughter of Major Sydney Edwin Bellingham, Middlesex Regiment. They had the following children:

Alan Ford b.1910;

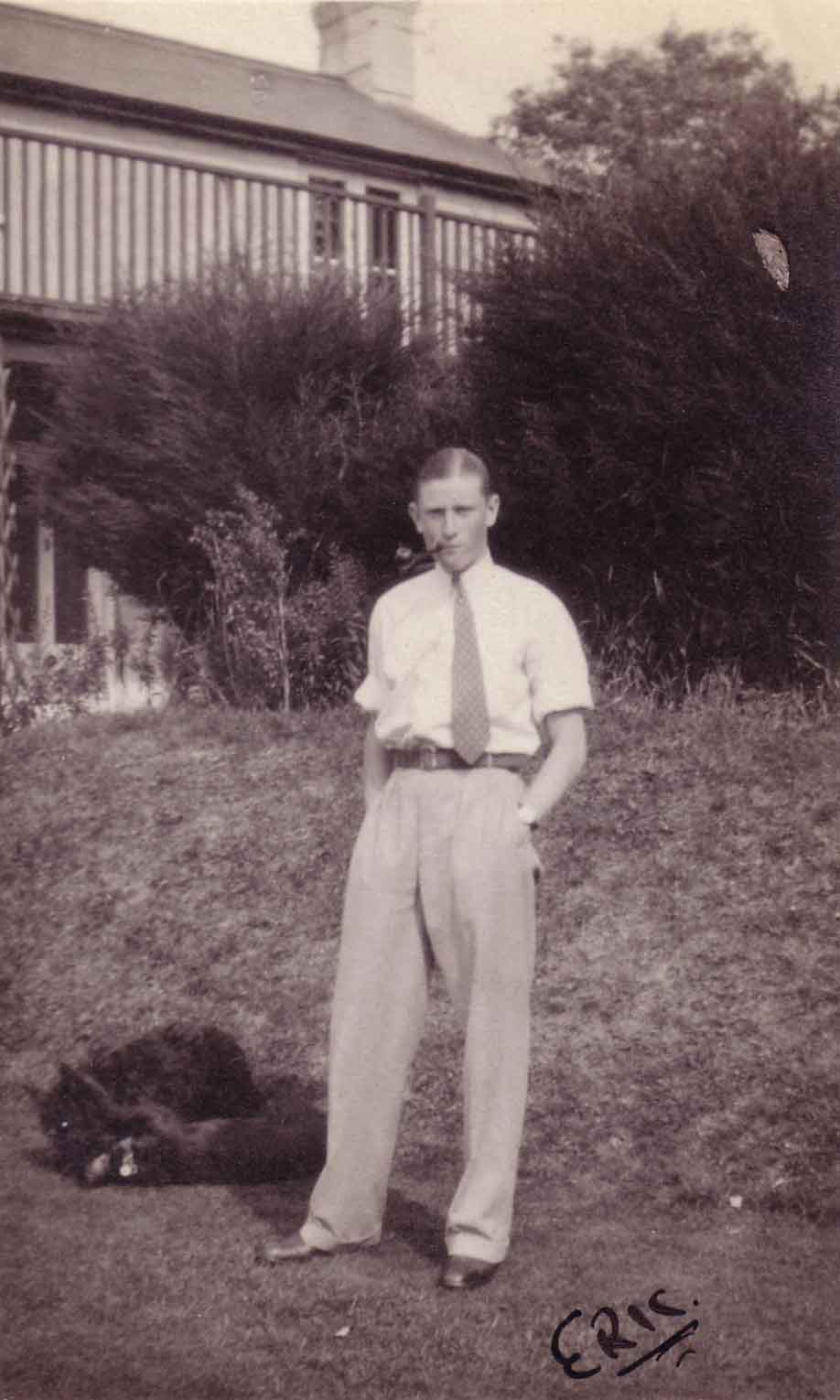

Eric Ronald Ford b.1919 [picture].F ii Eliane Gabrielle Ford [pictures] b.1875 at Belsize Park, London d.1964 at Worthing, Sussex, known as 'Aunt Lulla'.

Married 15 September 1908 at St Peter's Church, Hampstead Frederick Bovet b.4 September 1878 at 3 Victoria Street, London SW d.1956 at Worthing, Sussex.F iii Marion Gabrielle Ford b.1879 unmarried [pictures]. Known to me as 'Aunt Mingo'.

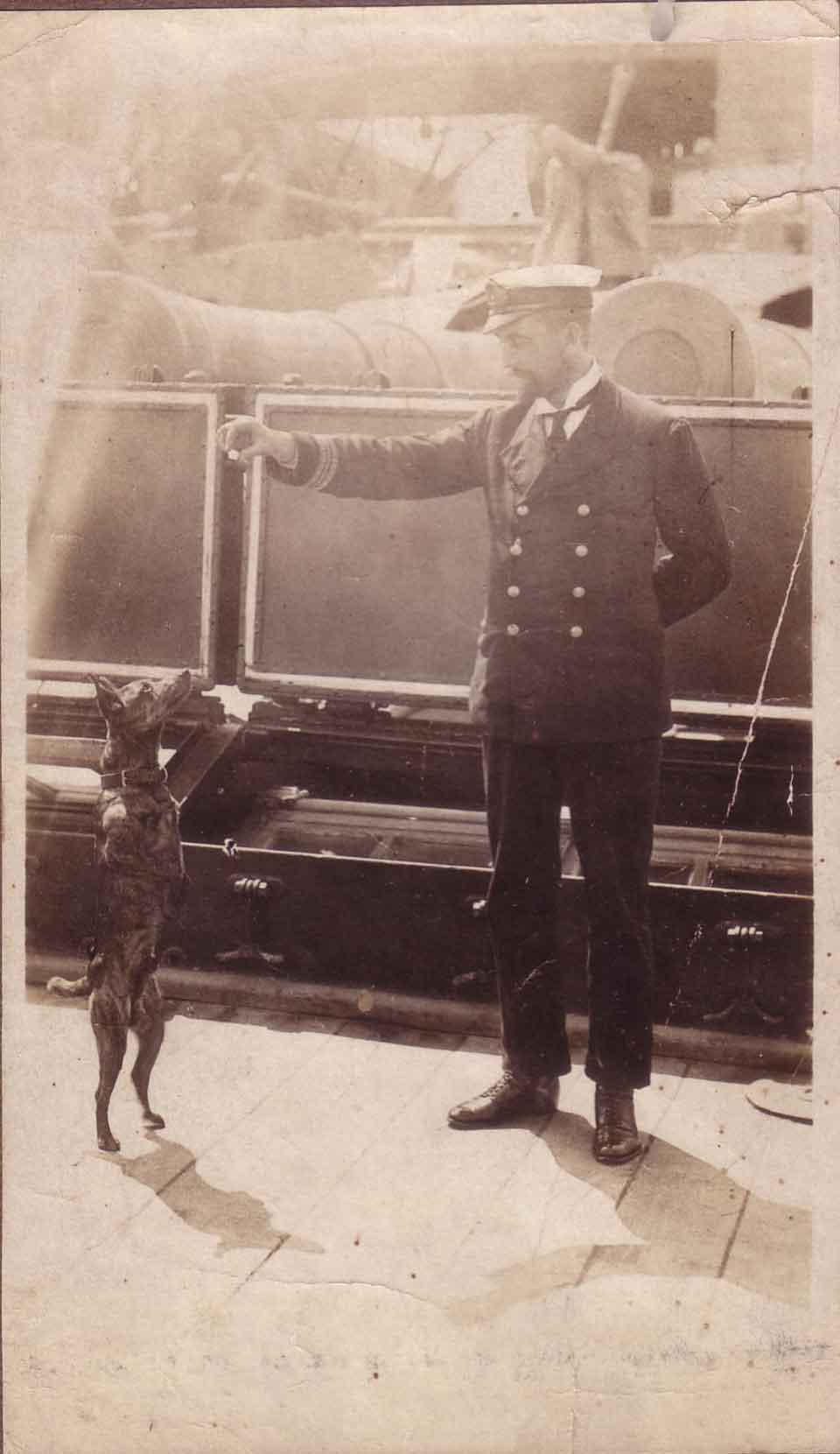

M iv Lieutenant-Commander John "Jack" Frances Ford RN b.18 May 1882 at Hampstead d.1939 unmarried [pictures]. Retired 1914 but came out of retirement to become a Captain in Inland Transport during WWI. F v Norah Ford. b.1891, who married in 1918 Ronald Brymer Beckett.

John Ford Anderson was LRCS Edinburgh 1861. MD Aberdeen1863. MRCP London 1926

at the age of 86. After leaving Edinburgh he was resident physician Middlesex

Hospital. London 1863-64 and studied in Paris and Vienna. He served in the Red

Cross with the German army in the Franco-Prussian war 1870-1 when he met his

wife. He then took a practice in Hampstead, London from which he retired in

1925. Chairman Hampstead Division of BMA for several years. President, Metropolitan

Counties Branch BMA 1904-5. In addition to his other work, he held charge of

St Marylebone Workhouse during two years of the First World War, operating several

times under fire during air raids.

Gabrielle Coudron John Ford met during the siege of Paris September 19, 1870

– January 28, 1871, where John Ford worked for the Red Cross. Gabrielle always

told her children to eat what was on their plate as much of Paris had starved

during the siege. The story went that only men who performed guard duty patrolling

the city walls would receive a bread ration, and this went very badly on those

with families. One night John Ford let a man with children take his place so

he could have the bread ration for his family, and that very night the man was

shot while patrolling.

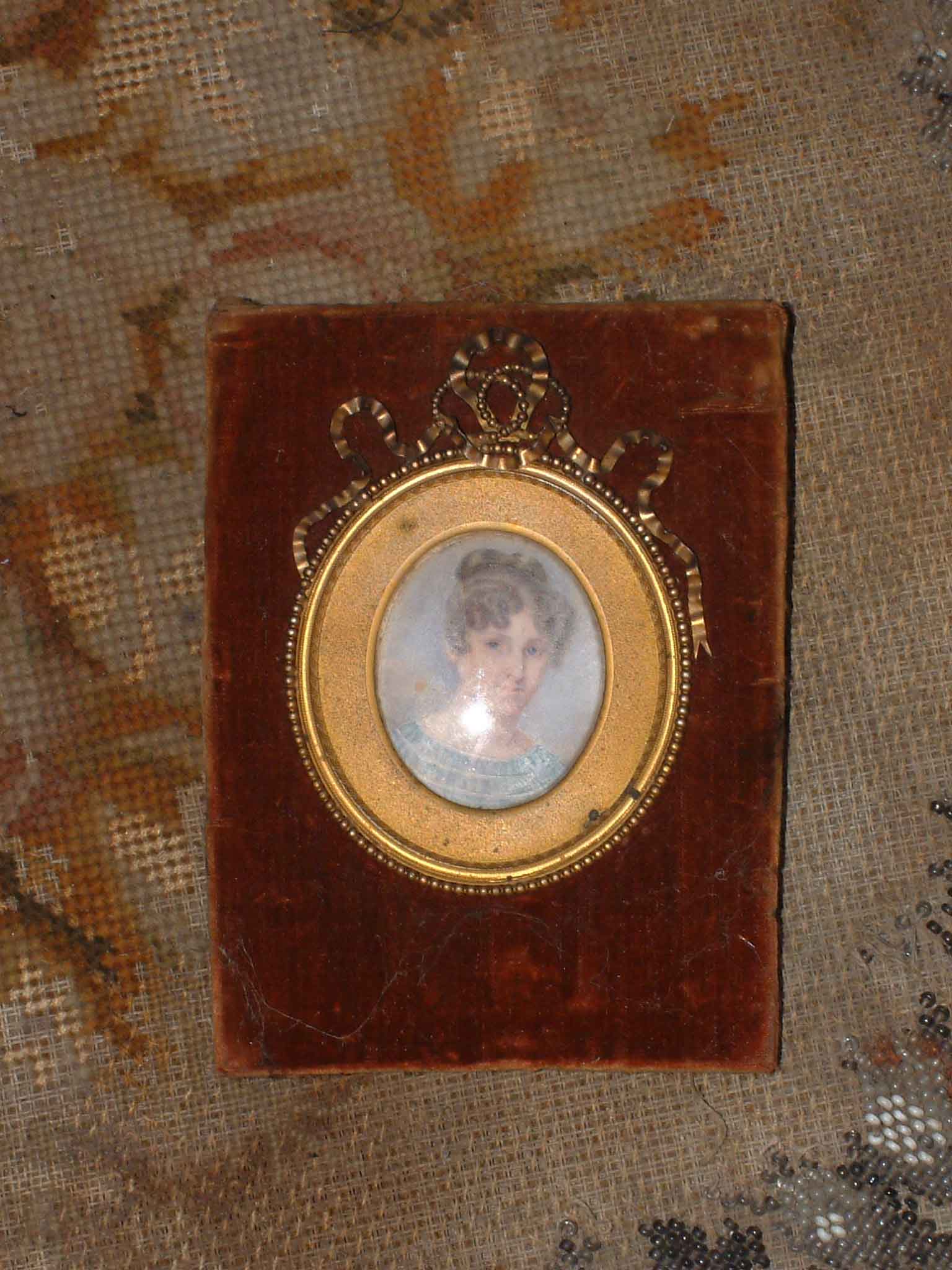

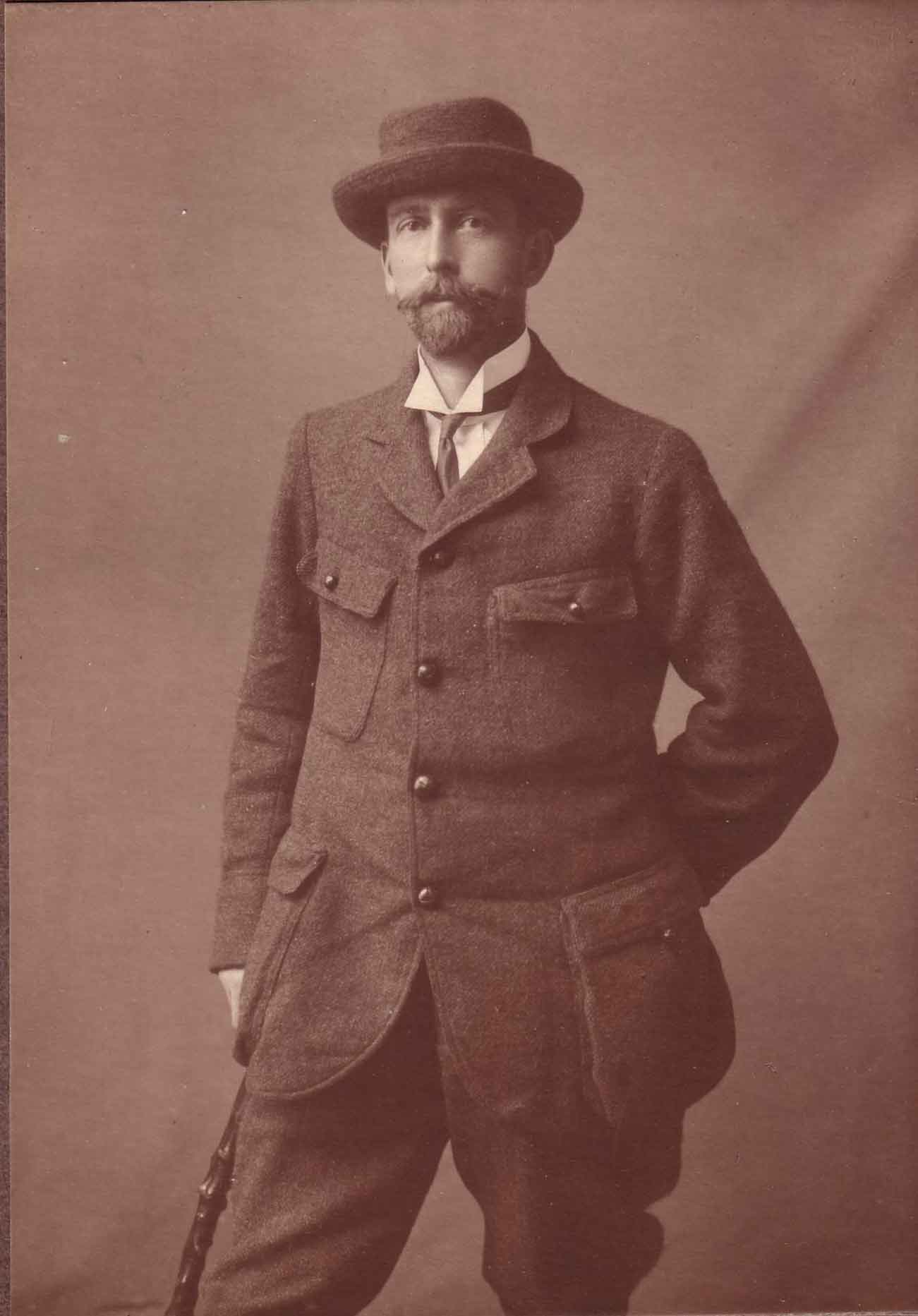

Gabrielle's mother (the Anderson family tree gives her name as Amédée

Coudron but Elisabeth Beckett called her Cécile) was supposed to have

been a 'warming pan baby' of the King of France, who needed a male heir. She

was therefore exchanged for an acceptable boy child and brought up by her supposed

mother, whose miniature is shown below.

Amédée Coudron

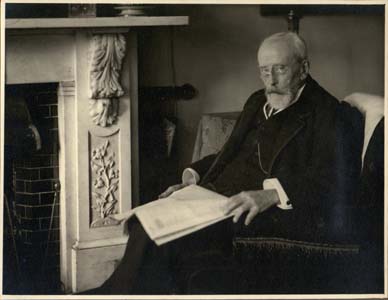

Dr JOHN FORD ANDERSON ( 1840 - 1933 )

Distinguished Son of Boyndie Manse

by

DR ALEXANDER A. CORMACK

His great grandfather was Alexander Anderson, medical practitioner, Jamaica Street, Peterhead, 6ft 3in in height, 23 stones in weight, known as Nosey by reason of a prominent feature - who, having served as surgeon on board the flagship of Admiral John Ford, called his son John Ford Anderson.

His grand-father, John Ford Anderson, 1784-1812, M.A., Marischal College, 1802, at age 18, M.D., medical practitioner in Peterhead, died tragically at age 28 of typhus, a scourge of Europe in those days. In the old churchyard of Peterhead I found his grave, covered by a lovely polished red granite stone inscribed: "To the beloved memory of John Ford Anderson, M.D., who died of fever, 27th April 1812, aged 28. His wife, Margaret Skelton died 9th December 1876, aged 86". erected by their children, Alexander, of Chanonry, Old Aberdeen; Mary, wife of Andrew Murray, advocate, Aberdeen; James, shipowner, London; Joan Ford, wife of James Yuill, minister of the Free Church, Peterhead.

The Skeltons of Invernettie were shipowners in Peterhead, where in 1961 you will still find a Skelton Street. Of the four orphan children, Alexander became minister of Boyndie 1830-1843; James was a cofounder of the Orient Shipping Company, and proprietor of Hilton and Middlefield estates, Aberdeen (a fine investment for feuing); a granddaughter of Joan, daughter of George Skelton Yuill, shipowner, became Countess of Portarlington.

We note that with better housing, better sanitation, clean water and clean food, medical science has conquered cholera, typhus, smallpox, tuberculosis and to some extent venereal diseases. Because Civil Registration began in Scotland only on lst January 1855, we have no records of deaths caused by those virulent diseases. But in Fraserburgh I found there was in 1866 a very high deathrate from Asiatic Cholera, an epidemic intestinal disease; of 57 deaths registered from 21st July to 14th October, 44 were due to cholera. Buckpool had a small cottage cholera hospital for incoming sailors. Banffshire used to keep a portable isolation hospital for infectious diseases. The small isolation hospitals in Braemar, Ballater, Forgue, etc., are now used to house district nurses. The Aberdeen City Fever Hospital, opened in 1877, to replace temporary hospital huts on the links, is now serving in 1961 as a General Hospital, mostly for the aged, like the Campbell Hospital at Portsoy. So too the small rural gifted hospital with half a dozen mixed beds, ill-equipped by modem standards, and expensive to staff night and day, is giving way slowly to the larger well-equipped hospital, with modern ambulances at the ready, and helicopters in the near future.

In exactly the same way, small schools cannot give their pupils a modern standard of education. With both nurses and teachers very scarce, we must change our outlook.

John Ford Anderson, M.D., who died of typhus at the age of 28 in 1812, would not have so died in 1961. His widow with her four very young cliildren went to St Andrews to serve as housekeeper to her oncle, Rev. Francis Nicoll, D.D., brother of her mother and Principal of St Andrew's University, son of a merchant in Lossiemouth, M.A. King's College, Aberdeen, 1789.

The older son, Alexander, was sent early life to work in an Edinburgh law office. Meeting in Edinburgh, James A. Haldane, ex-naval officer and minister of a Baptist Church, he returned to St Andrews to study Arts and Divinity. There he came under the influence of Rev. Thomas Chalmers, D.D., professor of Moral Philosophy, who in 1843 became the first Moderator of the Assembly of the Free Church of Scotland. In 1826 at age of 18, he graduated M.A., brilliantly, and in 1830 when not quite 22, he was presented to the parish of Boyndie by the earl of Seafield, patron of the parish, in whose family (Sir James Grant of Grant, Bart.) his grand uncle, Principal Nicoll, had served as a family tutor. He had been licensed as competent by the Church of Scotland Presbytery of Deer, which included his native parish of Peterhead. Up till 1874, when patronage was abolished with financial compensation to patrons for loss of privileges, a parish church congregation did not elect its ministers.

It was the parish patron who selected a safe man of his own political and social persuasion, whom he expected to support his own private views at all times. In this case the Earl of Seafield caught a Tartar, who led the Disruption Revolt in Banffshire in 1843. Himself descended from a naval surgeon, Alexander Anderson, minister of Boyndie married Mary Gavin (1806-1864), the third of eleven children of Dr Alexander Gavin, R.N., medical practitioner at Strichen, naval surgeon on H.M. Frigate "Arrow".

See photos below

Gabrielle Anderson 1850 - 1929 written by Eliane Gabrielle Ford Bovet née Anderson,

her eldest daughter.

I wish my mother could have been induced to write down herself some of the incidents she used to tell us of her childhood and youth. She always said, "They would not be funny, repeated," and so they have never hitherto been recorded.

One of her early recollections was of being taken by her father through the busy Paris streets, and taught how to cross safely among the swiftly-moving traffic, her hand firmly clasped in his. This early training never failed her in after life, and may have been a factor in the formation of a character remarkable for its promptness in taking decisions and acting on them fearlessly.

She used to describe to us the ordeal of having to act as "hostess" at her French school. Surrounded by the entire school, pupils and staff, one girl would sit and receive visits from others. There could be no awkwardness nor giggling, but conversation, bearing, and deportment had to be correct in every detail. That this system was not destructive of spontaneity and individuality was proved by my mother's charm as a hostess in her own home in later years. It probably gave her the poise and self-con?dence which freed her to express her own individuality and sympathy without diffidence, thus putting her guests completely at their ease. Her individuality must have been very marked from her earliest years. She said herself that she was a great trial to her old duenna, who escorted her everywhere when her mother was unable to do so, who called her "Mademoiselle," and whose admonitions were continually dissipated by the quick repartee of her charge.

Into the sheltered life of this French girl of sixty years ago, came the Franco-Prussian war, with its inevitable disruption of home life. She and her younger brother, Henri, with hundreds of bouches inutiles found themselves obliged to escape from Paris before the advancing German army. She described the scene at the railway station. Her mother had been hurriedly trying to gather what money she could from harassed bankers, and with the injunction "Get the tickets," left her at the end of a long queue of waiting travellers. "What tickets? " she in turn asked herself as she in her turn approached the guichet . She had never thought, nor had her mother, where they should go, but her quick wit decided: "To the coast, of course - to Havre." And so to Havre they went.

For what seemed hours after their arrival, their heavily laden conveyance drove from door to door, only to be met with the words., " No room." At last, after some parley at one house, a lady came out and looked into the omnibus. "l have a room for two people," she said. There was a rush for the door. " No," she said, " if there are two women together, l will take them." The room proved to be a small attic, and a corner was found somewhere in the house for the boy. When they were alone, my grandmother said; " This will do for to-night. We will ?nd something better in the morning." But they learned to be thankful for the shelter of that little room during the ?ve long months of the siege, while the guns thundered round Paris, practically cutting off that city from all contact with the outer world. Almost, but not quite, for, even in those early days, transit by air was becoming a practical proposition, and after the battle of Sedan, on September 1st, 1870, Gambetta rose above Paris in a dirigible, and ?ew to Tours, to rouse the Provinces to resist the invader, thereby prolonging the war for another year. Gambetta, after the war, became President of the Chamber of Deputies, but he was by profession an avocat, and in that capacity had often helped my grandmother in legal matters. His portrait, with the inscription:

" A Madame Coudron,

Témoignage de ma vive sympathie.

Léon Gambetta, '

which he sent to my grandmother on the occasion of the death of her son, Henri, is now in my father's possession.

A small feminine incident recurs in connection with their stay in that room in Havre. As the winter approached, with the need for warmer clothing than what they had hastily snatched when they left Paris, my grandmother told her daughter that she could afford to buy her the material for a dress, but that she must make it herself. And so the girl spread her material on the ?oor, and, totally inexperienced in the art of dressmaking, drew on it with chalk the outline of a dress and jacket, cut them out and sewed them by hand, and of what was left made herself a muff, a cap, and gaiters!

Havre proved a safe refuge, with the possibility of escape to England in case of need. But even there, the discipline rendered necessary by war was in full force. During those months a soldier convicted of stealing a cabbage was shot in the public Place in view of the assembled garrison. Of the privations and discomforts experienced during the siege by the citizens of Paris, they heard later from their friends. The mortality was chie?y among the very young children, as there was no milk for them. A donkey's head became a luxury, and cost something like £6, and rats were I facetiously advertised outside the shops as "Rat goût de mouton." The last animal to be sacri?ced was the well-known elephant in the Jardin D'Acclimatation, and the best of him was served to the German prisoners in Hospital, who, in addition to being well fed, were thus kept in ignorance of the true state of a?airs in the city. As an anti-climax, my mother's much-loved cat survived, for it was rescued from their flat by a woman to whom my grandmother had shown kindness, and kept with her own rabbits, and eventually returned to her. They learned how soon the people, except for the scarcity of food, got inured to the conditions under which they lived during the siege. A girl whose home was near the forti?cations used often, on her way to or from school, to throw herself flat on the ground when a shell, hurtling through the air, had spent itself, and then get up and go on her way.

When the siege was raised my grandmother brought her daughter to England, and, while she herself returned to try and recover her scattered possessions, left her in the care of some kindly people recommended by a business friend. This proved the turning-point in her life, as, within a year she married and settled in England. She married a young doctor, the third son of the Reverend Alexander Anderson, LL.D., of Old Aberdeen, who had lately started practice in London, and, during their long married life, although both he and she observed the absolute discretion inseparable from the work of a physician, she was ever ready as a friend and counsellor where her support was needed. The record of my father's life is too full of incident and of achievement in his profession to ?nd a place in what can only be ll very super?cial record of hers. It requires, and will certainly have, a place of its own, but it may he said here that, together, they upheld for their children the standard of honour, integrity, and breadth of vision in which they had both been educated, and maintained the tradition of true hospitality which drew to our home an ever increasing circle of friends.

My mother's early days in England, knowing nothing of its language and customs, cannot have been easy. The housekeeper who had looked after my father in his bachelor days stayed on to " help " her. My mother was instructed by her new sisters-in-law to feed their brother well - to give him plenty of meat, and her daily visits to the kitchen at ?rst got no further than " We will have mutton." "We will have beef." And, no helpful suggestions coming from the housekeeper, mutton and beef they had, until the mistress of the house learned enough English to propose some modi?cation of these viands - or the housekeeper was replaced by someone less unyielding.

During a trip to Scotland my father, after reading William Black's book, " A Daughter of Heth," wrote on the fly-leaf, " To my wife - to encourage her" and gave the book to my mother. This story of a French girl, transplanted from her own country and eventually married to the son of a Scotch minister, continually offending the conventions of the Manse, and having her own natural spontaneity as continually repressed, was too near reality at that time to be entirely encouraging. My father's point may have been that the French girl won her way into everyone's heart - my mother's was that she died of mental starvation; so the incident became a joke, and was recounted many times against my father. He himself said he always meant it as a joke!

One of the permanent jokes against her dated from those early days, when, on hearing some marital upheaval described, she demanded, "What then for did she do the transaction? " This phrase became a by-word in the family.

During her first weeks in England, before her marriage, she was riding one morning with her guardian in the Row, when an open carriage came along. She did not know that this was unusual. Hurried whispers to her to make way conveyed nothing to her, and her horse was unwilling. "I did not see why I should go to one side for a little lady in a carriage." she said. But an outrider settled the question by ?icking her horse on the hind-quarters, "And then," she said, "I saw that the little lady was the Queen, and she laughed to me so prettily." In later years it sometimes happened that, when driving in the Park, she was bowed to respectfully by passers-by, driving or on foot. The ex-Empress Eugénie, by then an exile in England, was well-known to the public, and my mother, with her clear-cut features and her white hair worn high from her forehead, was very like her, and was undoubtedly mistaken for her. But quite apart from that likeness, there was in my mother a charm and dignity which always compelled recognition and respect. In her earlier and more active days, she carried these with her wherever she went. As she became less able to move about, she seemed to become a centre, round whom many gathered. Nieces and nephews of two generations, friends, both men and women, would come and talk to her of their interests and their troubles and get in return wise counsel. That counsel was always sound. Unhampered by "theories " and creeds (in their narrower sense), her reasoning was logical and uninfluenced by personal considerations and opinions.

My mother's early artistic training had developed in her an unerring eye for line and colour. She studied in ]ulian's Studio in Paris, and later, she came to London, at the Slade School. Just as, on entering a picture gallery, she would glance round the room and instantly "spot" the painting that she knew was good, so, in more utilitarian matters, this sense would enable her instantly to pick out, somewhere in the recesses of a shop, the one thing that would satisfy her taste and suit her purpose.

She was a great worker. Very methodical in the ordering of her daily life, her time for thinking was also her time for needlework, and after her household duties were done , and her letters and accounts "polished off," as she expressed it, she would sew for the rest of the morning. We discovered that if we admired a piece of embroidery at the psychological moment, that is, when the date of its completion could reasonably be gauged, she would say - "All right, you shall have it when it is finished." And many of our houses have been beautified by her handiwork.

Her reading was as methodically ordered as everything else, and the hour before dinner, in the evening, was given to this, except during the years when the presence of two of her grandchildren in the house revived the "children's hour." At those times, she would again take her needlework, and while the two little girls played or or worked near her, she would tell them about bygone people and things and why things happened to people. That was the way she thought always. Events were only of value in relation to their cause or their consequences.

Her affection for her grandchildren she expressed in her own way. "Sonny" to her grandsons meant a very great deal from her, while " Miquette," the term of endearment she had used to her own youngest daughter in her childhood, descended to her two little girls for use in lighter moments.

She was for so long unable to get about easily that one is apt to forget her active days, but looking back, it all comes to one again. Our bus-top expeditions for shopping, or to visit picture galleries and museums; our calls, and our dances (very correctly chaperoned in those days!), and, nearer home, the various church activities, working parties and Christmas decorations; the yearly Christmas dinner at Frognal Park, the house of my father's uncle; and our frequent after-dinner visits to nearby cousins, where we children played hide-and-seek all over the house while our elders talked downstairs in the smoking room. I think the death of that brother of my father's and consequent breaking up of his home in London, was one of the greatest sorrows of my parents' married life, for "Gavin " was a staunch and valued friend, and his loss to my mother was irreplaceable.

The demands made by his profession on father's time unavoidably left many duties to my mother. It was she who visited the schools and interviewed the schoolmasters; who organised the family holidays and took us away (en bloc, and with the inevitable tin bath of that period, which always refused to shut at the critical moment when the growler was at the door); and yet who, among her manifold home duties, would be called to sit with a sick friend, or quiet an angry father indignant at the unreasonableness of his offspring, or, in one way or another, to pour oil on troubled waters.

The war of 1870-1871, which had come into the experience of that young girl, had made on her a lasting impression. It was to her always "The War" - until 1914. In the early August of that year, during the fateful week following the declaration of war between France and Germany, and when the world watched to see what England was going to do, all the intensity of patriotism for the country of her birth, which had been allowed to lie dormant in allegiance to the country of her adoption, reasserted itself. Her two sons were in the service of this country, one in the Army, the other in the Navy - a fact which probably intensi?ed her sense of responsibility in the decision which had to be taken. I was alone with her at her cottage in the country. On the wall was a large map of France, on which we were following that second advance of the German army upon Paris - that advance so miraculously checked. I shall never forget her emotion, she who in big things was always so calm. As she sat quietly sewing, she would exclaim suddenly, "Surely we are going to help them . We couldn't keep out … it would be a disgrace!" "We" was England always; and it seemed as if in this crisis her anxiety was for both countries - support and help for the one - and the honour of the other.

I have seen in two women of that generation, in my mother, a Frenchwoman by birth, in the other, one by adoption, a great hatred of the enemy that had humbled their country in that earlier war. It seemed for years as if that enemy could never be forgiven. But from the moment of the outbreak of the Great War, I never heard my mother say one word against the Germans. When the inevitable ebullition of hatred, malice and vituperation always engendered by war, filled the popular press, it evoked nothing in her, even in the light of past memories. Her only comment, when these things were spoken in her presence, was: "No, the Germans are now our enemy. They must be treated as an honourable enemy." Among her friends in England were many Germans, the wives or daughters of business men. It is significant of her feeling towards them that they came to her in any trouble. She understood them and what their position must be in this country, and they appreciated her never-failing sympathy and wise consel - and her sense of humour.

That sense of humour she always disowned. "I have no humour," she would say, "I have only wit." Whatever it was called, she had it in a marked degree. Her wit was quick and evanescent. She said herself she could never tell "good stories." She always missed the point. But none could describe better than she a personal experience. These were often told against herself. In her early days in England she was present at a dinner party at which Mr. and Mrs. Gladstone were the guests of honour. I cannot recollect what subject had been under discussion, but she had given her point of view with the assurance of youth, and it was not the view of Mr. Gladstone. A moment later a slip of paper was handed to her by a waiter, with the pencilled words, "We never contradict Mr. Gladstone." It was signed by Mrs. Gladstone.'

Talking of dinners - her brother-in-law, also of the name of Anderson, asked her to accompany him to the Lord Mayor's banquet, his wife being prevented by illness from going. They entered the room,

announced in the usual stentorian tones as "Mr. and Mrs. Anderson," and were greeted by the Lord and Lady Mayoress. Unfortunately, my uncle's fondness for truth intruded itself at that moment, and he proceeded to explain to their hosts, "This is not my wife . . . " when he was cut short and urged onwards to make way for the next comers-and there, it rested! '

My father had at one time an old coachman, called by us "The mummy." My mother came home one very hot afternoon, and described how she was sitting in the "victoria" outside my father's club in Piccadilly, waiting for him to join her. " l was in my best bonnet," she said, "and feeling no end of a swell, when the mummy fell asleep in his box. Down bobbed his head suddenly and his top-hat fell of into the road, and inside was a cabbage leaf! Served me right! "

[A question has now been raised as to whether was my mother who figured in this incident. Her description of it, however, has left such a vivid picture of herself as the offender that, in default of actual evidence to the contrary, I record it, without prejudice. E. F. B.]

A story of more recent times which she used to enjoy telling against herself was this:-

Distressed by the bad condition of the school-children's teeth in the village near her country cottage, she had the idea of demonstrating practically to them - and to their parents - the value of proper care for the teeth. A large number of toothbrushes was purchased on her behalf and served out to the children with instructions to use them daily, and a prize was promised to the child whose teeth, at the end of a given time, were adjudged in best condition. She secured the co-operation of her own dentist in London in the good cause, and in due time he came down and inspected every mouth, and the prize was awarded to the owner of a really good set of teeth. "What do you think? " said my mother with a twinkle, a few days later. "That child was away when it all started, and never had a toothbrush."

My mother to the end of her life never lost her French accent but I never knew anyone with a better command of language, either in speech or in writing. In her letters, which for their brevity could more correctly be called "notes" she had a gift of conveying just as much as she wished to convey - and no more - in a very few words.

I find in an old letter of hers:- "I am off to Mrs. B….'s At Home. It is fixed for tomorrow but I clothe myself in ignorance and go to-day." And again re household matters:- "I am not sure that spring cleaning should not be abolished altogether. It disturbs the dirt, spoils the decorations, adds to the breakages and upsets both the servants and the served. Two sweeps a year and a coat of paint or distemper every two years would be cheaper in the long run." …. "Cook has treasured up a pig-pail large enough to afford her a bath, and there were no less than three boxes of rubbish for her delight. You can easily imagine what I said and the peace of the house for the rest of the day." …. And another, on the subject of a parish sale:- "There was a book-stand which tempted me hard, but thinking of your reproachful looks, I refrained, and only bought some useful and fairly ugly things … I met Mrs. W… staggering under a large ill-made parcel quite in keeping with what we know as "distressed ladies." …. I went to Mrs. F…'s stall to honour her with my custom, but she was absent, and three or four girls like toothpicks stared me out of human kindness, so I fled."

And these written about two of her children :- "K_ _ _" (aged 4) "is very good for her. She says she has discovered a way to stop her naughtiness. 'I just say a little prayer,' and then she illustrates the thing_ by eating all the chocolates, then says a prayer. She is a promising subject!" And "I made an early start for Winchester, where I found J… was in disgrace for not working, and singing original versions of the Psalms in church."

Some of her spontaneous remarks, when recorded, might seem to defy the conventions, religious, artistic, or social, but as she made them lightly, and, as it were, on the wing, they never seemed to shock any susceptibilities. I remember a call made at the house of some art-loving friends. They had brought back from their travels several photographs of the "Madonna and Child" by the old Masters, and these had been mounted in a long frame and placed in a conspicuous position on the wall. 'Oh dear! " said my mother when she saw them, "Bureau de nourrices."

At a farewell dinner, given to one of her nephews before his departure for Australia, she was sitting on his right hand. On his left was another aunt, of progressive tendencies. In those days smoking among women was almost unheard of, but this aunt, always in the vanguard of unconventionality, lit a cigarette. "Don you see what she is doing?" whispered the horrified young man. "Max," said my mother, unmoved, "you should never tell your right hand what your left hand doeth."

Many a serious situation was leavened by her wit. When the time approached for my con?rmation, she elected to receive instruction, as I did, from our old friend, Dr. Edgar Sheppard, then Sub-dean of the Chapel Royal, a most broad-minded and loveable man, and to be con?rmed with me. I th1nk even then l recognised the courage of her action, taking her place for con?rmation among a company of young people of i5 to 17 years of age. We drove down to St. James' with Mrs. Sheppard, who said to my mother as we arrived at the chapel, "Dear, some smuts have blown on to your face … let me brush them off." "Why of course," said my mother, "it's the conversion of the Blacks."

To her nephew, Dr. Francis Barker, whose care and devotion helped so much to lighten the burden of her last illness, she paid one of her spontaneous tributes: "Frank can do me no good now," she said, "but he goes through the house like a south-west wind and leaves us all feeling better and happier."

She kept her courage and her humour to the very end. A great friend who had seen much of her during her last illness, came to see her as usual, a few days before she died. She had that morning realised that she could no longer struggle against increasing weakness, and said she knew she must go. She had a week before had a fall in her room, and one side of her face was much discoloured. "Just imagine," she said to her friend, " having to appear before the Almighty with a black eye! "

We used to think her impatient in small things. If she was, it was the quickness of a mind irked by the slowness of her environment. The decisions she reached by a lightning process of reasoning were reached by slower and more circuitous avenues by her more phlegmatic family. But as years went on with their mellowing in?uence, it was her qualities of sympathy, tolerance, and in?nite patience which made her the valued friend to so many. In her last days she said:-"I should like people to think well of me when l go. Do you think they will? " She has her answer in the tributes of a very great number of friends.

To her patience and her courage in the greater troubles and anxieties of life, no words can do justice. Her maxim was, " If you are ill or unhappy, stay in your room. Do not in?ict it upon others." And she kept this rule in the spirit if not in the letter, by ever presenting a brave front to the world, whatever lay behind.

It has been said, " They are not made like that now." They are, sometimes, but tradition and example have surely gone far in the making.

E. F. B.

John Ford Anderson (2) b.1840 d.1933 and Gabrielle Coudron d.1929 aged 79

More photos below

Taken at Olive Galsworthy's house just before the radio broadcast by J.F.A.

From left: Unknown lady, Mr Galsworthy, Olive Galsworthy, John Ford Anderson, ? Milne, with Marion Anderson standing at the back.

More photos below

John Ford Anderson with Auckland and Belle Geddes

More photos below

Gabrielle Coudron d.1929 aged 79 #1

More photos below

Gabrielle Coudron d.1929 aged 79 #2

More photos below

Gabrielle Coudron d.1929 aged 79 #3

More photos below

Cecil Ford Anderson b.1872 d.1946

More photos below

Cecil Ford Anderson b.1872 d.1946 and Maud Alice Bellingham on their weddng day. Marion Ford Anderson is second from the left.

More photos below

Cecil Ford Anderson b.1872 d.1946 and Maud Alice Bellingham with their children Eric Ronald Ford Anderson b.1919 and Alan Ford Anderson b.1910

More photos below

Cecil Ford Anderson, Mrs Bellingham, Gela, Maud holding Robin, Alan Anderson.

More photos below

Eliane Gabrielle Ford Anderson b.1875

More photos below

Marion Gabrielle Ford Anderson b.1879 Maggie

Smith, Cecily Booth, Marion Anderson, Henrietta Livingstone, 4 schoolchums at

54 Belsize Park

More photos below

Left: Mr Cuchullain, Gabrielle Coudron and Marion Ford Anderson outside 41 Belsize Park, the Ford Anderson home, and (right) Robert Bevan's painting of 'A street scene in Belsize', 1917, thought to be the same building.

More photos below

Young John "Jack" Frances Ford Anderson b.1882 d.1939

More John "Jack" Frances Ford Anderson below

Lieutenant-Commander John "Jack" Frances Ford Anderson RN b.1882 d.1939

More photos below

Norah Ford Anderson b.188 d.19

More photos below

Eric Ford Anderson b.1919